Suspended Sentences

Suspended Sentences

Turners Warehouse, Newlyn, Cornwall

12 - 22 September 2013

Venue

Turners Warehouse

Of all the public places, dear

To make a scene, I’ve chosen here

The first line of this excerpt from Simon Armitage’s poem ‘Give’, is written on a shutter with a peephole, looking onto a bench outside Turners Warehouse. The bench bears the inscription from the second line of the poem, (changing the pronoun from ‘I’ to ‘We’): ‘We’ve chosen here’ [1].

Armitage’s poem ‘Give’ initially appears to come straight from the pleading heart of the poem’s protagonist to a potential lover. It is only on a second reading, the meaning shifts to form the internal monologue of a homeless person to an ambivalent passerby. I would like to take these two lines further out of context, in the climate of this art review, to say a third (mis)reading is that it aptly describes the motivation to be an artist, live in a specific place, find like-minded others to form an art scene, and to make and show work in that place to an audience who may or may not expect to want it. ‘We’ve chosen here’.

Exemplifying this community-minded approach, ‘Suspended Sentences’ has been a large artist-led group exhibition and series of events including experimental film, music and sound nights, taking place at Turners Warehouse in Newlyn, Cornwall. An old unused fish processing factory, the warehouse is currently under a suspended sentence of its own, biding time in planning department limbo awaiting a decision on plans to transform it into an art house cinema [2]. The show’s title references poet Simon Armitage’s past employment as a probation officer, or as Armitage added on hearing it, could be reminiscent of poetry being written in zero gravity.

The exhibition forms an open response to Armitage’s poetry, after his recent walk along the South West coast path from Minehead to Land’s End with his last mainland reading happening at Newlyn Art School [3]. Regional artists [4] were invited by the project’s curators Mark Spray and Jesse Leroy Smith, to take Armitage’s poetry as a departure point or to explore the idea of a journey. Rather than be illustrative, the artists were encouraged “to in a sense fall between the lines”.

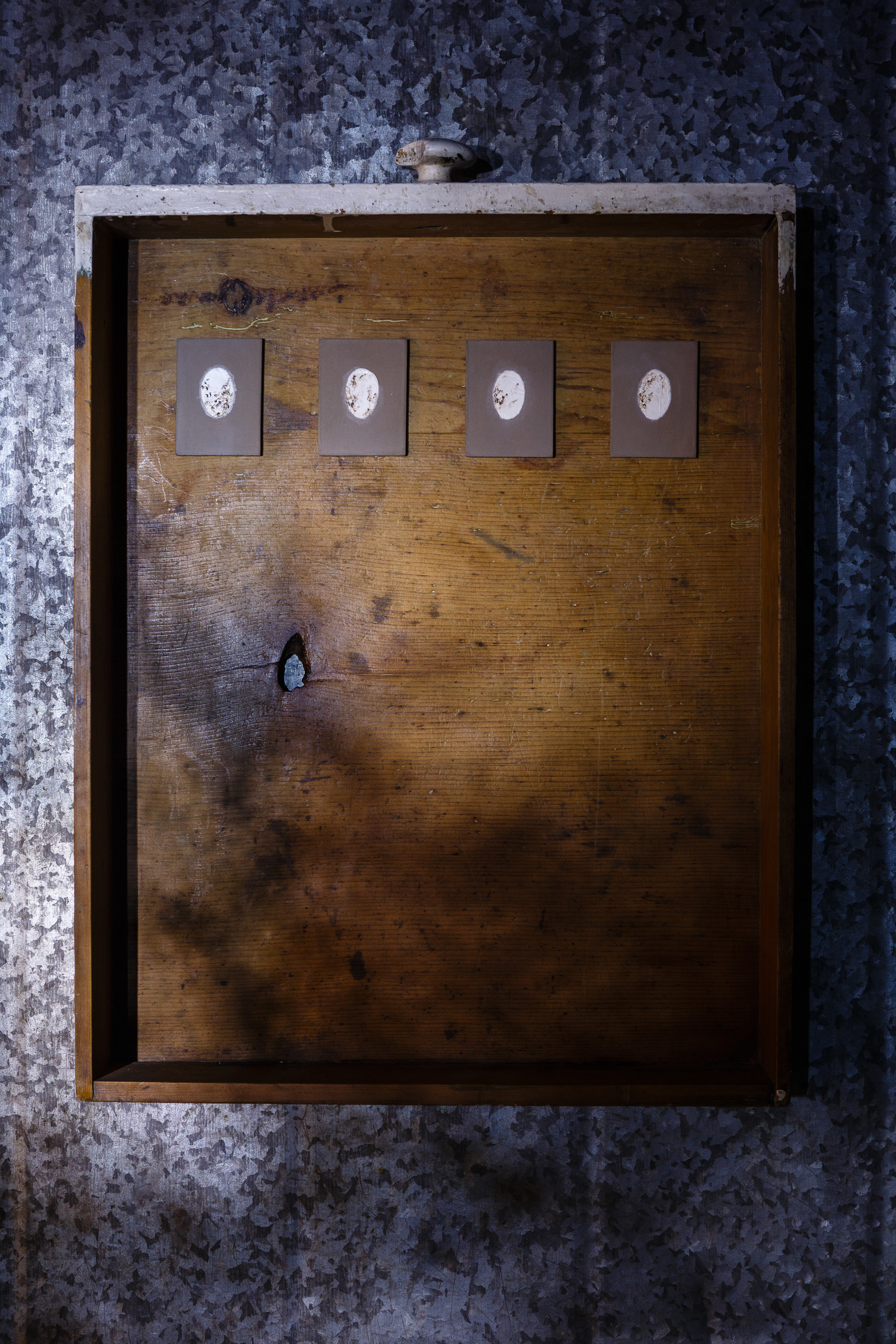

The two month process of clearing and cleaning the building, undertaken by the curators and artists, has definitely paid off, leading to a familiarity of the architectural topography, with a sense of the right works inhabiting the right spaces. Mark Spray referred to this synchronicity of placement occurring “where the building demanded it”. Projected onto an old-fashioned slide screen, Mark Jenkin and Oliver Berry’s ‘Talking Coast’ film is viewed as if peering over from one coastal promontory to another, standing on a step at the room’s threshold, held back by a gridded barrier; whilst ‘The Jay’, an animation by Oscar Lewis and Oli Mason, is perched on a screen placed up in the rafters. Mark Spray’s own work ‘Nature Boy’s Sanctum’ is the first work to be visited in the main building. Viewed by torchlight, a tree is cradled concisely in the dark volume of a freezer room, offering the first encounter with a transformed place. The delicacy of the small paintings of eggs that line the walls surrounding the tree also suggest the fragility of being held. Jayne Anita Smith’s print ‘Black Box Study’, positioned discretely next to a small boiler, also presents an encounter with something out of place, showing a figure on a beach, confronting a strange modernist black box.

Across two floors of the main building- including freezer rooms, the sick room and an ice chute- then further along the street into a garage and road freezer, there is a sense of a journey unfolding as you make your way through. Happened upon as the institutional upper corridor prepares to turn into a bitumen blackened corridor, Tom Rickman’s epic filmic sequence of small, square, immaculate paintings, ‘Marsala’, details a road trip across Sicily, capturing glimpses of poplar trees, roadside crosses, sunsets, and the perspectives roads narrowing at the horizon line.

The traces of past use of the warehouse are still apparent and in places cleverly utilised into gallery fittings. The opaque white plastic strips of a freezer room doorway become the ubiquitous curtain of a video room; an old cooling system unit has a projector incorporated into it. Elsewhere a fish weighing set of scales lies in the corridor. Above it, an ‘Insectaflash’ fly exterminator is dormant, replete with past catches.

Of all the doorsteps in the world

To choose to sleep, I have chosen yours

I’m on the street, under the stars

‘Give’, by Simon Armitage

Some of the works respond to the traces of this building’s past life. Faye Dobinson’s lightbox ’1483 Misses’, as a spinning ellipsis of dots, could be a segment taken from the speeding time lapse starry constellations of Scilly night skies in Graham Gaunt’s film ‘Dark Nights 2′. Yet Dobinson’s piece has more prosaic origins, to be found up in the Observatory Room of the warehouse, as the exact number of holes and positions made by wide-of-the-mark darts encircling an absent darts board.

Other works directly respond to specific works by Armitage. Paul Fry repeatedly returned to Armitage’s ‘The Not Dead’, a poem about the numbness of veterans coming back from war: ‘Soldiers with nothing but time to kill/ we idle now in everyday clothes and ordinary towns’. A regiment of chiselled graphite pieces stand erect in little compartments on the left wall of another of the warehouse’s freezer rooms. Directly opposite, the lines of the poem have been written so many times with the graphite on a large sheet of paper that the words fall and are lost in its dark field. Positioned quietly on the back wall is one large, smooth, black stone positioned on a simple stand or alter. Fry has placed Paul Norris’s work ‘Touchstone’ here. It is made from serpentine stone, which is known as the ‘infinite’ stone. As a single object within the space it could reference something larger than us; a religious relic, worn by touch. Equally, within the poem’s realm of ‘The Not Dead’, this touchstone could represent the cold ‘Britannia’ that the soldiers worship, then are spurned by, on their return from war.

You give me tea. How big of you.

I am on my knees. I beg of you.

Give, by Simon Armitage

A number of pieces echo the unavoidable darkness at the core of many of Armitage’s poems. In ‘The Blackened Corridor’, Sarah Ball’s ‘Accused’ portraits form a line up; a sequence of mugshots of innocuous looking offenders, from a youth with glasses and a sheepskin coat to a rotund middle aged man in a suit and a fashionable young woman with a dark fringe, decorated head scarf and orange coat. Marie Claire Hamon’s painted trinity of vehicles quietly on fire are hung over a part of the concrete wall which is replete with crudely scribbled male and female body parts. Both firelighting and graffiti as disenfranchised occupations suggest too much time to hand and little to do. Jesse Leroy Smith’s ‘Under the Influence’, comprises of forty portraits of those participating or linked to the show, from the artists themselves to the building’s owner. These portraits have a visceral and bruised quality to them. Applied to copper, the paint has been actively pushed around and wiped off in places. In two works found next to each other, the first is of one of the artists as a child, clutching a toy; the second is of the same person as an adult, with a bandage over one eye following an assault.

The works in ‘Under the Influence’ can be read individually but also as an extended community portrait, or a community of influence, a theme which plays through with the inclusion of one of Armitage’s heroes, Seamus Heaney in the show. ‘My Heavy Head’ is a sculpture Tim Shaw made of the poet. Written nearby is the phrase ‘Noli Timere’, ‘Don’t be afraid’, Heaney’s last words to his wife. Michael Rees work is also situated in the same partitioned office. The singular figures that inhabit his impasto surfaces have a lonely air about them, ‘Creatures of a different stripe-the awkward, unwanted, unloveable types’. [5] John Maltby has, on Rees’ website, written that the artist ‘scrapes and scours [the surface] until an image perhaps a figure is exhumed from the surroundings.’ Rees’ work is beautifully situated with Heaney’s 1973 poem ‘Tollund Man’, who was an unknown Iron Age man excavated from a Danish peat bog by P.V. Glob in 1953.

The voiceover in Mark Jenkin’s film ‘If this is no-one’s then its ours’ asks the question, ‘How should we define public space?’ It goes on to list some answers, including ‘a place where people can congregate…. a place of cultural collectiveness’. This collectiveness and desire to create a public space is very apparent in the structure and energy of the whole enterprise of ‘Suspended Sentences’, through the fundamental personal choices to be making and showing contemporary work in this area, to the wide inclusion of artists at different points in their career from recent graduates to the more established, and the social heart of a cafe and series of events also adding to the opportunities to come together and spend time in this building over the duration of the project. The exhibition also offered an experimental space for a number of the artists to work with different mediums from their norm. One, Jayne Anita Smith, highlighted that for her the community aspect of ‘Suspended Sentences’ had allowed her to ‘tap into that energy, giving the motivation and drive to push further’.

It’s not as if I’m holding out

For frankincense or myrrh, just change

Give, by Simon Armitage

An early talking point out and about was the economic decision to charge an entry admission of £4. During Simon Armitage’s own journey, which involved twenty-four readings, a hat was passed round for people to contribute to, in order to show their appreciation. For the two curators of ‘Suspended Sentences’, it has been important to set a fee for this artist-led venture which has not received public funding. In much the same spirit as Armitage’s gesture, the purchase of the ticket has been a way to represent the value of the venture and been a necessary investment that people have made, going towards overheads. The importance of properly valuing the generous grassroots economy of the visual arts is succinctly stated in Nom de Strip’s recent article:

And if as audiences and participants, visual arts is something that is important to us, something that we want to play a role in our private and public lives, then we all need to consider what we are doing to make it happen. This need not be onerous or pricey, but it does require an honest acknowledgement of both its value and cost. [6]

Jenny Brownrigg, September 2013

Footnotes

1 ‘We’ve Chosen Here’, James Pankey and Arabella Pio

2 Planning application for Newlyn Arts Cinema was approved by Cornwall Country Council 21/10/13

3 Newlyn Art School is an independent venture set up in 2011 by Henry Garfitt

4 Given that Armitage’s poems are studied as part of the curriculum it is fitting that Cape Cornwall School were also invited to respond

5 From’The Not Dead’, Simon Armitage

6 ‘A Culture of Giving’, Anna Searle Jones, Nom de Strip